A Nerd Visits the ER with His Apple Watch – Twice

Life with an Apple Watch

Using the Apple Health Export data to show the context of a visit to the ER.

A disclaimer: Not only am I not a cardiologist, but if you asked me to point to the location of the heart in my chest, I wonder whether I would point to the correct spot. Perhaps the information presented here may be of some use, but I don’t have the expertise to say one way or the other.

During my talk at RConf 2022 I briefly described both of these episodes. Here I’ll provide a bit more detail about how I used data from the Apple Health Export to provide some context for what went on before and during these visits.

At the ER in February 2019

I feel a tinge of embarrassment about this ER visit because one can argue it was not necessary. But in part by accident it had favorable health consequences. I started my conference talk with this visit, although a problem with my microphone means the story at the beginning is missing.

About 1:30 AM, that is, in the middle of the night, in 2019 I had a brief but intense period of digestive upset. I won’t go into the details except to say that it probably was related to GERD and that I have had episodes somewhat like this since I was in my late 30’s (although much diminished as I got older because of change of diet and acid blockers).

About 5:30 AM after a brief visit to the bathroom I got back into bed and felt strange, looked at my Apple Watch, and saw that my pulse was up to 150. I felt my pulse at my throat and realized the reading was not a fluke. Now comes the embarrassing part. I freaked out. I don’t claim my alarm was reasonable. I had no chest pain or any other symptom except rapid pulse. I was half asleep and not thinking clearly. I immediately jumped out of bed thinking I needed to go to the ER and told my partner. If the same thing happened today I would not feel I needed to rush off like that, but I didn’t know any better then.

The ER was only 10 minutes away. During the drive I felt that my heart rate had dropped somewhat. We arrived at the ER at a time when it wasn’t very busy and after a quick stop at triage I was in a bed getting an ECG, which was normal. I told them that I felt my heart rate had been sustained at a fast rate until part way during the trip to the ER. That’s what I thought, but part of the point of this post is that we’ll see that my perception (and what I reported to the ER doc) was not accurate. I reported my digestive episode from earlier in the night and a blood test showed that my lipase (a pancreatic enzyme) was abnormally high. Eventually I realized they were less concerned about my heart and instead poking my abdomen. The doctor wqs considering whether I had pancreatitis, which I had never heard of. (Not only am I not a cardiologist, I also am not a gastroenterologist.)

Apparently the lipase level was abnormally high, but not as high as one would expect with pancreatitis. It turned out I didn’t have pancreatitis. I redid the blood work the next day and it was completely normal. Let’s ignore the digestive story because that turned out to be uneventful. Instead let’s focus on heart palpitations, the symptom that I presented with at the ER. (I haven’t had a significant repeat of the digestive episode since then so it doesn’t seem to be an issue I need to worry about. I regularly take acid blockers for GERD.)

I am not 100% clear about the meaning of the word “palpitations.” Generally it seems to imply a sensation of irregular heart beat, but the Wikipedia discussion suggests it also covers an abnormally rapid heart beat alone, which is the most I could muster in this case.

So what was actually going on with my heart rate during this incident? That takes us to the Apple Health Export. After getting home from the ER I was a bit unsettled by the whole experience and my characteristic reaction was to gather data.

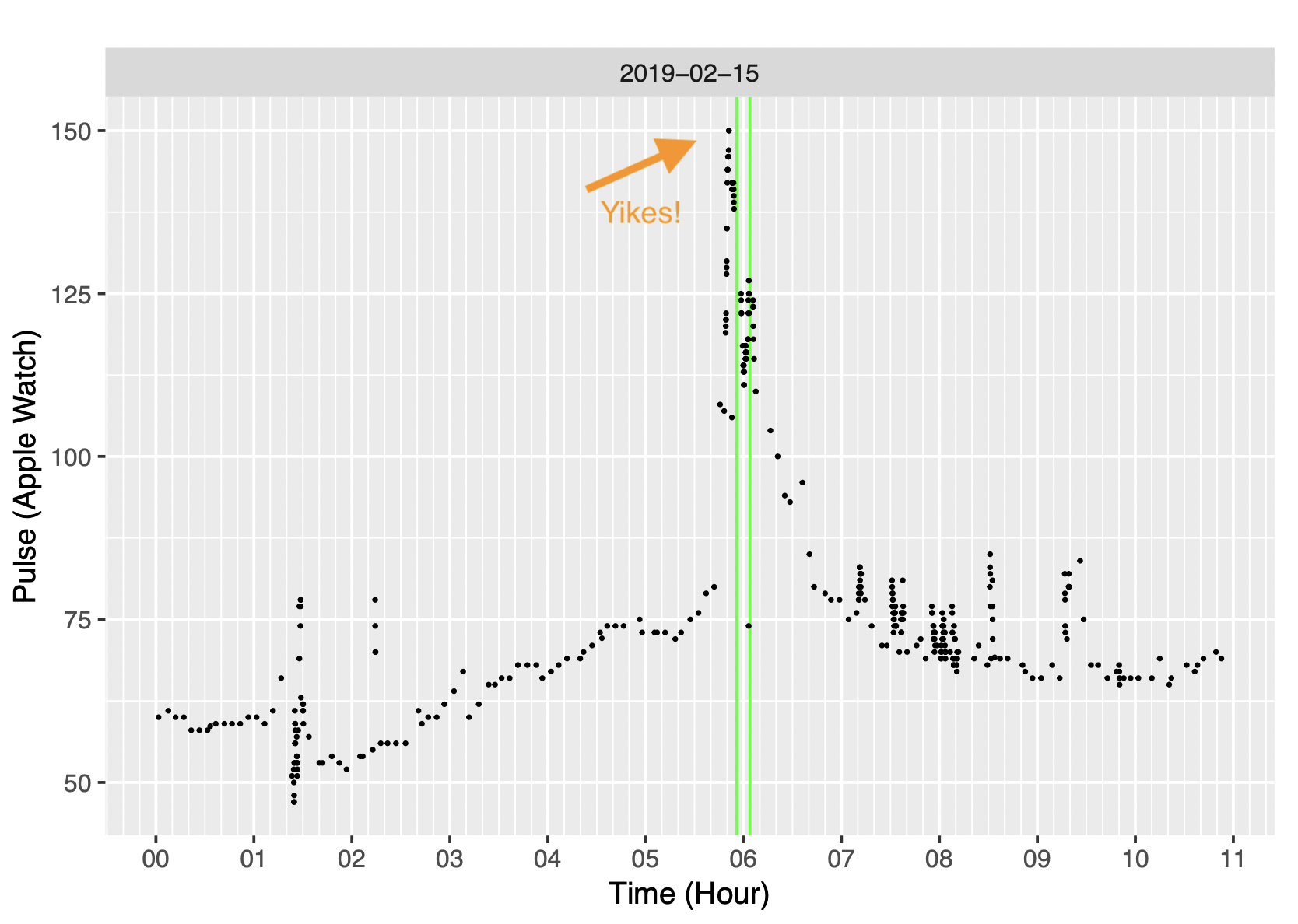

I also want to point out that the heart rate plot showed me that what I told the doctor when I arrived at the ER was not quite right. I told them that my heart rate increased suddenly and stayed high for a while. That was my perception, but the plot shows that actually it spiked to 150 and then immediately started going down. At the time I didn’t look at the pulse in my watch in part I think because I didn’t want to alarm myself. I suspect if I had looked at my watch and seen how much my heart rate was decreasing I would have calmed down and possibly not gone to the ER.

While I was at the ER, I looked at the simple heart rate history that is provided by the Apple Watch when you click on the “current” tab in the Heart app. It doesn’t really allow you to see the trend over time. To illustrate what that display looks like, shown here is a screenshot of my Apple Watch in an afternoon after I have taken my daily walk. It shows heart rate readings broken down by 30-minute intervals. When there’s a lot going on within a 30-minute interval basically what you see is a solid bar for that interval with the low and high heart rate. The result is a fairly muddy view of what is happening. During a workout (and often when there are substantial changes in heart rate), the watch is recording heart rate every few seconds. With the default display, you don’t see that level of detail.

I wish I could show you a screenshot from my time in the ER, but at the time I don’t think I knew how to make a screenshot from the Watch, and I had other things on my mind. I could see that my heart rate had been high and maxed out at 150. I couldn’t see clearly what had happened right before I arrived at the ER.

I was looking for better Apple heart rate data and that led me to learn about the Health Export. I vaguely knew that Apple was recording my heart rate so I did a bit of searching on the internet and discovered a post by Ryan Praskievicz that showed me how to get the Health Export and load it into R. At home I prepared for my follow-up visit with my primary care physician by creating a detailed record of my heart rate during the day in question. See my earlier post for a description of how to use R to download the Health Export and import and set it up in R. I acknowledge this is not something a normal person is going to do. I had a an appointment with my primary care physician early in the next week, and before that visit I had prepared a plot showing my heart rate throughout the incident, as recorded on my Apple Watch.1

I’ve included the actual figure that I took with me when I went to see my primary care physician after my visit to the ER (although the editorial “yikes!” was added later to add drama to my talk). In this figure, 00 is midnight. I had a brief but severe digestive episode at about 1:30. Later while I was still asleep in the early hours of the morning my pulse rises to about 75 and then at 5:30 I hit 150, which is quite noticeable for someone my age.

Is this home-made heart rate chart clinically useful? It certainly wasn’t the primary information that my physicians used. I subsequently did a 30-day event monitor to check my heart and had an MRI of my abdomin. I haven’t had a repeat of anything like this event, so that’s a good thing. From my personal point of view, the figure does suggest to me that there was a connection between the digestive even and the later brief episode of high heart rate tied together by the gradually rising heart rate while I slept. But who knows.

The visit to the ER did have one significant unintended consequence. As I was watching closely what I was eating in the days after the visit, I slipped into using LoseIt? to count calories and ended up losing about 25 pounds, as I’ve described in another post. it also caused me to take the time to learn how to use the Apple Watch to do an ECG. In my experience it takes a bit of practice to do a reliable reading. For the first incident I didn’t even try to do an ECG, although under the circumstances that would have been an appropriate thing to do.

So that’s the story of my visit to the ER in 2019. All in all it’s not a very exciting story, but that’s what one hopes for with a visit to the ER, at least if you’re a patient.

At the ER in October 2020

At the end of my RConf talk I also describe a second visit to the ER about a year and a half later.

I was sitting having lunch. Halfway through I felt odd and realized my pulse was high. I did an ECG and the Watch told me “Inconclusive”. At that time the Apple software was unlikely to say “Afib” if pulse was above about 110. They improved their software for the release that came out in December of 2020.

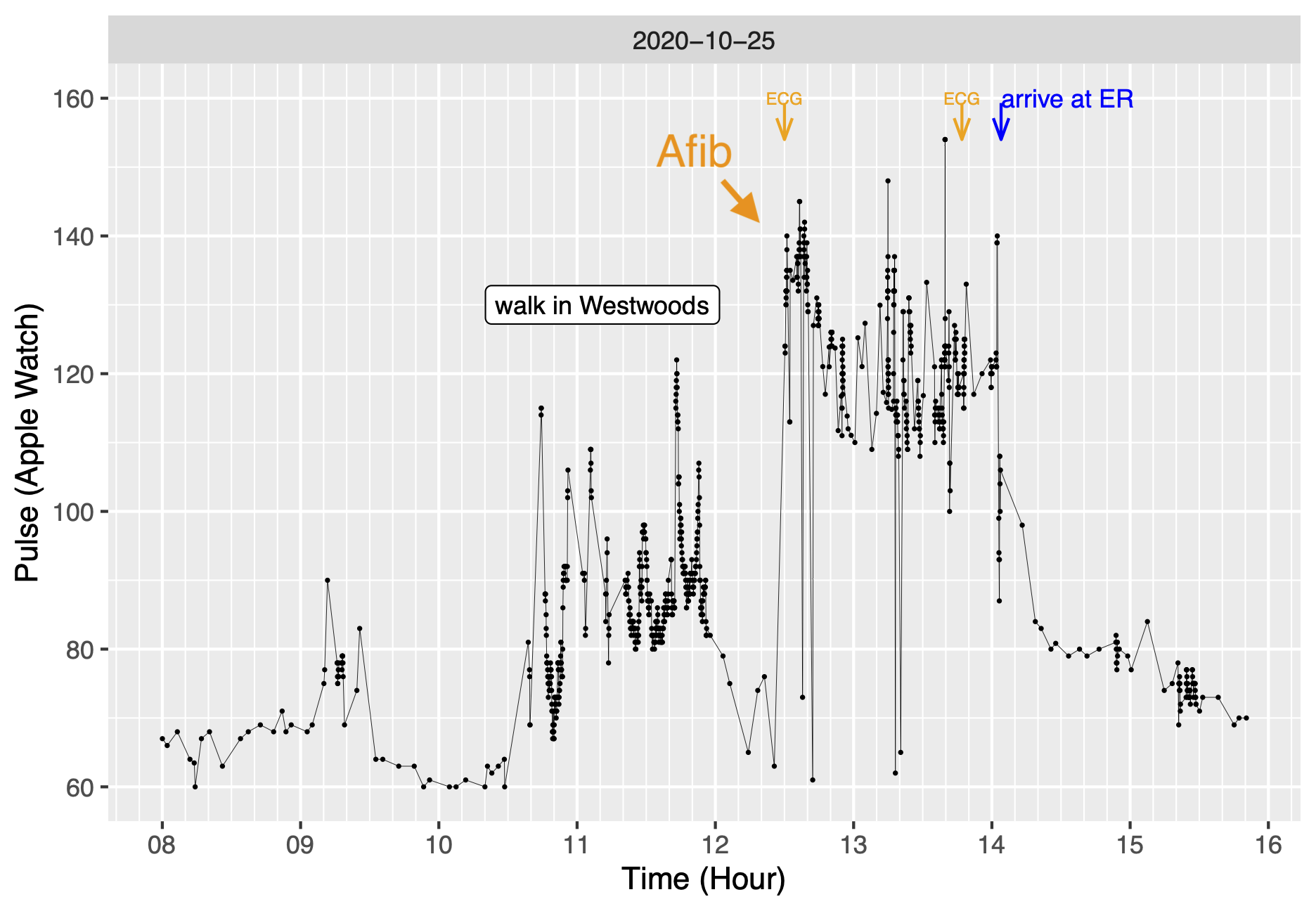

What I experienced at lunch felt similar to what I remembered of my previous episode of atrial fibrillation five years earlier. I did an ECG multiple times and it kept saying “inconclusive.” After I told my partner we were going to the ER I tried one more time and that time the watch did indicate atrial fibrillation. The’s the ECG I had on a slide for my talk. We drove to the ER which is nearby. I think I may have still been in Afib while I was talking with the triage nurse, but by the time I was hooked up to the EKG my heart had returned to normal rhythm (which medical types refer to as sinus rhythm). The farther up the medical food chain I went the less interest there was in whether my Watch had indicated Afib. Sometime later when I was referred to an electrophysiologist, she looked briefly at the ECG exported from the Apple Health App and said, yep, that’s Afib. I wore a 30-day event monitor again to check for signs of Afib that I was not aware of. Nothing turned up.

I did an chart of my heart rate during the day of the Afib episode. There are some marks at the top that flag when I did an ECG. The Atrial fibrillation started just before 12:30. It shows fairly clearly with on the plot. There are a couple of very low pulse readings, but that’s because my heart rate was irregular. It also makes it clear that I left Afib as suddenly as I went into it.

As I said in the talk, although I have the detail of the ECG record, there’s nothing I can do with that data. I included a small bit of the ECG strip as one of the slides in my talk. I think I see that the width of beats vary in the Afib ECG strip, but that doesn’t tell me anything.

But the all-day heart rate plot did have some value when I was discussing this with the electrophysiologist. The issue was whether I needed to go on blood thinners. A principle concern with Afib is that it increases the risk of stroke. Patients who frequently are in Afib are put on blood thinners to reduce that risk. If I’ve only had two episodes of Afib in seven years, then blood thinners may not be worthwhile in my case because blood thinners themselves create some risks. I would guess that my doctor relied primarily on the negative finding of my 30-day heart event monitor as evidence that I was not having Afib I wasn’t aware of. But I also pointed out that the chart showed how quickly I became aware of the Afib event when it started, and that was one more piece of evidence that I was not having Afib without knowing it. So the way we left things was that I would not take a blood thinner. That was almost two years ago and so far so good. We’ll see.

(In the spirit of using one’s own data, it also helped that I had been taking my blood pressure almost daily for several years. High blood pressure would increase the stroke risk from Afib. In the doctor’s office my systolic blood pressure was 160. I had data that showed my average was more like 125.)

In neither ER visit did my Apple Watch make any dramatic contribution to my medical care. But it may have provided information that was mildly helpful. In the examples here it provided an all-day context for an event that caused me to go to the ER. It certainly helped me to have a fuller understanding of these events.

Footnotes

The actual ER incident was not a major health event, and it may be legitimate to view it as an unnecessary ER visit. But it resulted in a significant improvement in my health via a route which also has an RStudio connection. When I left the ER, the doctor suggested that I might want to go on a liquid diet for a day or two. I didn’t know what a doctor means by a “liquid diet,” and I still don’t. But for a couple of days I subsisted on juice and broth. I wanted to avoid fatty food so I started using the LoseIt! app to track fat in what I was eating. I noted that I immediately lost a noticeable amount of weight without much difficulty. So for the next year and a half I faithfully used the LoseIt! app to track calories and ended up losing about 25 pounds. One of the creators of LoseIt! was J.J. Allaire, the co-founder of RStudio. It’s possible that losing that weight has lowered my blood pressure and improved my health in general and discovering RStudio has improved my intellectual health as well. The weight loss was an indirect result of the visit to the ER. For more, see my post on my experience with counting calories with LoseIt!.↩︎