if (file_exists("~/Downloads/export 2.zip")) usethis::ui_stop("More than one version of export zip.")

if (file_exists("~/Downloads/export.zip")) {

rc <- unzip("~/Downloads/export.zip", exdir = "~/Downloads", overwrite = TRUE) # exported folder is 2.75GB

if (length(rc) != 0) {

# once unzipped, delete export.zip. Otherwise, the next time Air Drop sends export.zip

# to your mac it will be renamed as export2.zip and you may accidentally process

# an out-of-date set of data.

# takes a bit more than 20 seconds on my iMac

health_xml <- XML::xmlParse("~/Downloads/apple_health_export/export.xml")

# takes about 70 seconds on my iMac

health_df <- XML:::xmlAttrsToDataFrame(health_xml["//Record"], stringsAsFactors = FALSE) |>

as_tibble() |> mutate(value = as.numeric(value)) |>

select(-device) # device seems to cause some duplicate rows

check_count <- nrow(health_df)

health_df <- health_df |> unique() # unique adds at least two minutes. Had found 42,364 rows, mostly Lose It!, SleepMatic, and Omron, but some came from Watch and iPhone

dup_count <- check_count - nrow(health_df)

usethis::ui_done( "Extracted {nrow(health_df)} rows for health_df. Removed {dup_count} duplicates.")

activity_df <- XML:::xmlAttrsToDataFrame(health_xml["//ActivitySummary"], stringsAsFactors = FALSE) |>

as_tibble()

usethis::ui_done("Extracted {nrow(activity_df)} rows for activity_df.")

workout_df <- XML:::xmlAttrsToDataFrame(health_xml["//Workout"], stringsAsFactors = FALSE) |>

as_tibble()

usethis::ui_done("Extracted {nrow(workout_df)} rows for workout_df.")

ecg_df <- dir_ls("~/Downloads/apple_health_export/electrocardiograms", glob = "*/ecg*.csv") |>

map_df(read_ecg_headers)

usethis::ui_done("Found info for {nrow(ecg_df)} rows for ecg_df.")

clinical_df <- XML:::xmlAttrsToDataFrame(health_xml["//ClinicalRecord"]) |>

as_tibble()

usethis::ui_done("Extracted {nrow(clinical_df)} rows for clinical_df.")

if (file.exists("~/Downloads/export.zip")) file.remove("~/Downloads/export.zip")

usethis::ui_info("Completed raw import, nrow(health_df): {usethis::ui_value(nrow(health_df))} ")

} else usethis::ui_stop("unzip returned a zero length list.")

} else usethis::ui_warn("There was no export.zip file.")Notes for RStudio:Conf 2022 Talk on Apple Health Export

Some items to supplement the talk at RStudio::Conf2022.

The video for the talk at RStudio::Conf2022 is available at the RStudio website, and I’ve also inserted a playable version on this page. There was a problem with the microphone at the start of the talk so the first couple of minutes are missing, but I’m probably the only one who will notice.

rstudio::conf 2022 Talks - An Introduction to the Apple Health Exports - RStudio

During the last several years I have been accumulating various notes while I explore the Apple Health Export. This post will be a series of disconnected comments. I’ll be adding to it during the weeks before and after my talk at RConf2022.

The schedule for the 2022 RStudio conference is here. My talk WAS at 11:30 on Thursday, July 28.

Here are the slides for my talk, done as a Quarto presentation.

To learn how to get the Apple Health Export and load it into R, see my first post in this series. Or see this more succinct and to the point version from a well-known R blogger.

This is post is not a coherent essay about the Apple Health Export. It’s just a series of unrelated thoughts that have some connection to the topic of my conference talk.

Some Observations Following the RConf Talk

Although my talk may give the impression that I spend my time hanging out in emergency rooms, I’m basically a healthy guy. I had a very short episode of Afib in 2020, but it has not repeated since then so for now it’s not a concern.

The talk basically came off the way I hoped it would. I was nervous about watching the actual video. Now I enjoy watching it primarily because it shows I’m having a good time. Watching myself have a good time makes me feel good.

Speaker Training

RStudio required speakers to participate in training and coaching for the talk. That involved four two-hour Zoom sessions. I appreciated the advice and guidance of Acacia Duncan of Articulation. As a life-long procrastinator, I have never been so prepared. The investment in the sessions had the indirect effect of raising the stakes for the talk and that was an additional push to do a good job. It was interesting to see the final version of talks that I had a glimpse of during training.

Back To My Pre-Talk Notes

If my posts on the Health Export seem self-centered, I admit they are. I’ve been in that mode for a long time. See An Implementation of Narcissism in R (and I’m a day or two away from doing an updated version of that post). I have been recording my weight each morning for more than 25 years. I appreciate that may be a bit odd and unusual. From my point of view, looking at my data in the Health Export is a continuation of the sort of thing I did from collecting data on my own. One value of the Apple Health Export is that it collects data from multiple sources. These days I use a Watch shortcut to record my weight each morning. Before I had the watch shortcut, I used to record my weight on a calendar each morning and then periodically transfer the data to a spreadsheet. Now I get that weight data via the Health Export. In a similar way, I used to record my blood pressure in a spreadsheet. I also use an app that transfers data from my blood pressure cuff to the Health app via a blue tooth connection and rely on the Health Export for that data as well.

The Big Picture

Dr. Sumbul Desai is Apple’s Vice President for Health, which makes her the spokesperson for the importance of the Apple Health Kit and the health data collected by the Watch and the iPhone. In an interview in February of 2022, Dr. Desai emphasized a quote from Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, which stakes out an ambitious claim:

If you zoom out into the future and you look back and you ask the question what was Apple’s greatest contribution to mankind, it will be about health. [at 2:05 in this interview]

That’s a bold statement. Apple has a long way to go to match that aspiration.

In May of 2022, David Pogue did a fun interview with Dr. Desai on CBS Sunday Morning that makes the case for the Health app. They spend some time on detection of atrial fibrillation, and I’ll have much more to say on that topic below. The electro-cardiogram is more directly a medical measure than the other measures taken by the Apple Watch. Perhaps that’s wrong-headed. For all I know, the machine learning required to reliably do fall detection or to measure walking unsteadiness may be more complex than what’s required to identify atrial fibrillation from the ECG. But understandably Apple emphasizes atrial fibrillation because it’s the most dramatic example of a direct connection between the Apple Watch and medical treatment.

The segment also includes an interview with Dr. Michael Snyder, a professor at the Stanford Medical School. Snyder’s topic is closer to the near term uses of the Apple Health Kit. He hopes to use health tracking to identify what’s “normal” for an individual so that one can detect changes that indicate that something now is not normal and intervention may be useful. Easier said than done. He talks about using health tracking to support early detection of COVID infection. Snyder did a TEDx talk on wearables all the way back in 2015. His point: “You don’t run your car without a dashboard. Here we are as people running around without any sensors most people and we should be wearing these things in my opinion because they can alert to early things.”

Large Scale Studies Using the Apple Health Data

I’m optimistic about what large scale studies might be able to find. The Apple iOS for the iPhone includes the Research app. The Research app is intended to facilitate large-scale studies that make use of the collected in the Apple Health Kit, the database that supports the Health app. I participate in the Apple Heart and Movement Study. The Research app is intended to support sharing of health data with a research project in a way that also protects the privacy of the data. So far the list of open studies looks underwhelming.

The Apple Heart Study has been completed and may serve as an example of how such studies can work.

There is also competition for the Apple Research app. MyDataHelps is a platform independent app that also manages collection of data from tracking to support research studies. I’m enrolled in the DETECT study by Scripps Research which is intended to see whether heart rate, activity, and sleep measured by my tracker can predict when someone is coming down with a viral illness even before they feel bad.

In the spirit of writing these notes, I just signed up for Project Baseline which appears to be the equivalent app created by Google.

A friend of mine is enrolled in the Johnson & Johnson Heartline Study. This study is looking at screening for atrial fibrillation. He was able to buy an Apple Watch at a reduced price to enter the study. (Otherwise they would have loaned him a watch.) I was not able to join this study because I have been previously diagnosed with atrial fibrillation.

I think these kinds of studies have a future. The most obvious places where they will be conclusive is the relationship between fitness and health. What trackers are really good at is measuring movement and heart rate. There’s a potential for studies that make very precise connections between intensity of physical activity and health. It may take longer for them to be effective in other areas.

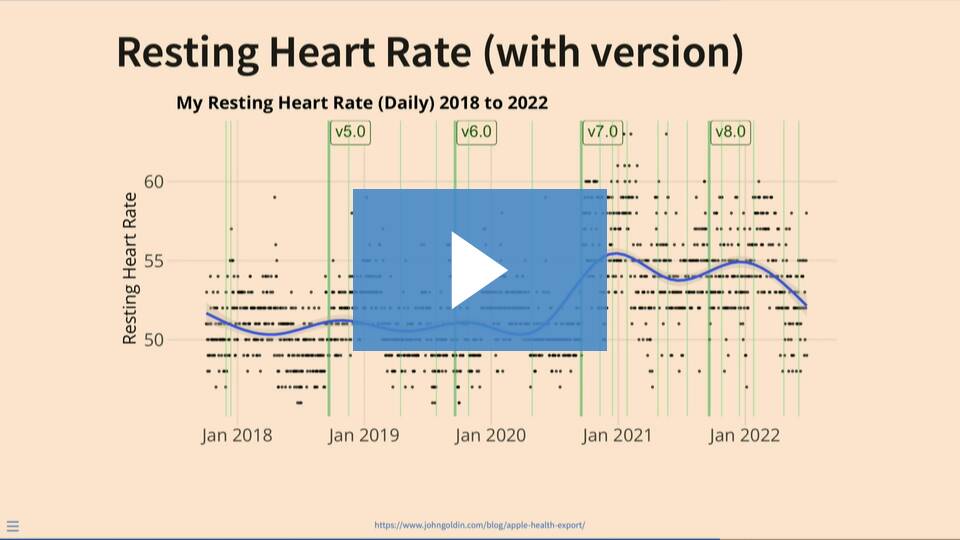

One problem with using Apple Watch data as the basis for research is that the measures are a “black box.” Apple is not forthcoming about the operational definition of the measures (i.e., what exactly are they doing) or whether the measures are changed. It’s a good thing that Apple makes changes in order to improve their measures. It’s a problem for researchers if they don’t know those changes are happening. There is an article in The Verge that describes an example of the problem.

While looking for information on Apple Watch studies, I also came across reports of early results from a study at the University of Michigan.

In summary, fitness and health trackers have potential to be important research tools. But we are still in the early days of those uses. Note that my perspective is that I am very much a personal user, and I have no experience with the research studies except as a subject.

Privacy

The Apple Health Kit is a moment by moment recording of your life. It has obvious implications for privacy. I may be the wrong person to evaluate the risks. As I look at my Health Export data, I do so wrapped in a cocoon of privilege that protects me from many of the potential consequences. I’m old enough that my future is limited. As a financially comfortable retiree I’m unlikely to apply for a job, unlikely to run for office, unlikely to encounter law enforcement or the criminal justice system. Perhaps some day Health Kit data could be used to question whether I should continue to have a license to drive. (And maybe that would be an appropriate use.)

In general I don’t feel like there’s much potential for adverse consequences for me personally. But I may not be typical. In the wake of the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade there has been much discussion of how cycle tracking in health apps could be used to expose women to prosecution. That’s not far fetched. January 6 rioters were tracked in part via their phone, but one can image that minute by minute heart rate data might also relate to their activities during the event. What could Communist China do with the Health Export data? It takes the invasion of privacy imagined in 1984 to another level.

I acknowledge that privacy of health and fitness tracking is a serious issue. But you shouldn’t look to me for a lot of wisdom on that aspect of tracking. I’ve already made a choice and immersed myself in tracking. It works for me, but my situation would not apply to everybody.

One practical issue is that if you extract the Apple Health Export you should pay attention to where the exported folder ends up. Apple emphasizes end-to-end encryption of the health data. Once you have extracted the data from the Apple Health app you are no longer protected by Apple encryption, and it becomes your responsibility rather than Apple’s to limit whether anyone else has access to it.

Atrial Fibrillation and the Apple Watch

Atrial fibrillation is an irregular heart rhythm that begins in your heart’s upper chambers. Afib is strongly related to age. “Prevalence increased from 0.1% among adults younger than 55 years to 9.0% in persons aged 80 years or older.” [from a 2001 study] Younger populations should not worry too much about atrial fibrillation.

Apple touts the value of widespread screening for Afib, but there are sound reasons why that might not be a good thing. Here’s the inconclusive statement from the US Preventative Care Task Force: “For adults 50 years or older who do not have signs or symptoms of atrial fibrillation (AF): The USPSTF found that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for AF.” Aaron Carroll, The Incidental Economist, has done a video expressing skepticism about the value of the ECG feature of the Apple Watch.

And for another skeptical note, see this article.

If you have symptoms, get it checked out. But if you don’t have symptoms, screening for Afib may not be worthwhile, especially among non-elderly populations.

I’ve had two episodes and the second was almost two years ago. So far atrial fibrillation has not been a big issue for me, and I hope that continues.

Apple and KardiaMobile from AliveCor

Note that in terms of personal detection of Afib, Apple has some significant competition. A company called AliveCor makes a product called KardiaMobile. I does an electro-cardiogram in a way that is similar to the Apple Watch. You can pick one up on Amazon for about $79. I just saw that there’s a new version called the KardiaMobile Card that is exactly the size of a credit card, presumably so that it will fit into your wallet.

The Skeptical Cardiologist discusses the use of both KardiaMobile and Apple Watch in his practice.

AliveCor has been maybe six months ahead of Apple in terms of what they’ve been able to detect with their software. When I had Afib in 2020, Apple’s algorithm would not say anything beyond “inconclusive” if pulse was higher than some level (I think only 110 or so.) AliveCor was doing better at high pulse rate. Apple got FDA approval for their improved algorithm at the end of 2020. AliveCor is now detecting some rhythm conditions other than Afib that Apple doesn’t detect. So AliveCor seems to be legitimate competition.

AliveCor is suing Apple for anti-trust actions in connection with their competition with Apple. I’m in no position to judge the legal merits of the lawsuit, but in moral terms they seem to have a point. AliveCor had developed a watchband for the Watch that would do an electro-cardiogram and they were selling that before Apple announced their ECG option. Normally Apple is secretive about future products, but AliveCor alleges that Apple pre-announced their ECG product in order to squelch AliveCor’s watchband product. Based on my limited reading, I have the impression that the KardiaMobile has a good reputation among cardiologists.

In March, a court ruled that AliveCor’s claims were sufficient for the case to proceed to trial (or at least I think that’s what this ruling means).

White, writing for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, cited claims that Apple intentionally “made it effectively impossible for third parties to inform a user when to take an ECG” through an update “to all earlier Apple Watch models” that “did not improve user experience.”

The update’s “purpose and effect” was allegedly “to prevent third parties from identifying irregular heart rate situations and from offering competing heart rate analysis apps,” the judge wrote Monday. “Plaintiff’s allegations plausibly establish that Apple’s conduct was anti-competitive.” (Bloomberg Law, March 22, 2022)

FDA Approval

I was curious what FDA approval of the Watch electrocardiogram looks like so here is the request for approval from the FDA, and here is the actual approval.

The Verge did an explanation of why Apple needed FDA approval for the electrocardiogram but did not get the pulse oximeter approved as a medical device.

Here is a list of six FDA approvals of electrocardiogram features in Watches.

A Bit More on the Nuts and Bolts of the Apple Health Export

The export from the Health app comes as a zip file called export.zip.

When I unzip export.zip I get an apple_health_export folder containing the following items:

apple_health_export (3.8 GB)

electrocardiograms [folder] (37 MB)

export_cda.xml (851 MB)

workout-routes [folder] (1.3 GB)

export.xml (1.7 GB) <– the part I use

I always make sure I unzip this in my Downloads folder, which is excluded from my Time Machine backup. I don’t want to clutter up my backup with all these gigabytes of stuff. (But see my comment above on why you should be aware who has access to this folder.)

My first post has more detail on getting the export.

Below is a fragment of the code I use to do the actual import of the data from export.xml.

I have a bunch more code after this that does some basic setup of the data.

I realize I should do a Github Gist to share this code.

In my first post on the Health Export I go into a lot of detail about the time stamps. Briefly, the time stamps appear to be saved in UTC time zone and converted to local time when you do the export. As a result, activity in a different time zone will appear to be at a different time during the day. Plus if you do the export after a change to daylight savings time, all the time stamps will be adjusted by one hour. Usually you can ignore this, but if you are focused on sleep tracking or nighttime resting heart rate (something I’m interested in), you need to watch out for this.