Part 4 Navigation and Finding Your Way

Don’t Lose Your Way

Finding Your Way

For the official long-distance routes on the coast, navigation is easy. Just keep the ocean to your left (or right, depending on your general heading). And yet on the first day of setting out from Padstow on the South West Coast Path I managed to follow a finger post that said “SWCP” that pointed in the direction opposite from my intended direction. It’s hard to explain how I did that. I won’t bore you with a long paragraph on how I turned myself around. The point is that it’s possible to get off track.

My most important piece of advice is don’t be over confident and assume you know where you are. When in doubt, check. You’re on foot so if you continue in an incorrect direction it can take you a long time to fix your mistake. Better to notice quickly that you are off your intended route and do something about it sooner rather than later. So how do you know where you are and whether you are on track?

Maps

The Ordnance Survey is the government organization that does maps for the UK. OS paper maps are widely available in bookstores and local shops. The OS Explorer series is aimed at walkers. The scale is very tight: 4cm on the map is equal to 1km in the real world (a scale of 1:25000).

A paper map at that scale turns out to be fairly bulky and unwieldy. I confess I have almost never used the 1:25K scale OS maps. Instead on multi-day walks I have relied on Harvey Maps, whose slogan is “a good week’s walking on one map”. Harvey maps are available for the national trails and some popular long routes. The scale is 1:40K rather than 1:25K. There’s enough detail to find your way, but it’s easier to get the map unfolded so that you can see the spot you need. They are printed on waterproof paper, a good feature for a map you plan to need for a week.

The Ordnance Survey also offers the OS Landranger series, which is useful for walks but with less detail and less paper. At a scale of 1:50K you can see a much larger area for a given size of paper. It’s not as detailed as the Explorer maps, but it’s generally good enough to help you find your way. If you are spending a lot of time in a location not covered by a Harvey map, the Explorer maps are a good alternative.

Maps on Your Phone

To find your way using a paper map you need to locate where you are on the map. One attractive feature of a map on your phone is that the GPS can show you where you are on the map.

The Ordnance Survey offers access to their maps on Android or iPhone via their OS Maps app. My first opportunity to use the iPhone OS Maps was in 2023. Before that I used other electronic aids, primarily AllTrails on my iPhone and a Garmin GPS (or SatNav in Brit speak) loaded with Open Street Map for the UK obtained via an outfit called Talkytoaster. Based on my experience of using the Ordnance Survey OS Maps app on my iPhone in 2023, I expect that will continue to be my main tool in the future. Access is by subscription, a 14-day free trial, then $28.99 per year ($2.42/month), which is a good deal. By comparison, a single Landranger paper maps costs £8.99.

The app mimics the appearance of the paper Ordnance Survey maps. If you are looking at a wider area, the format follows the Landranger series (where the paper maps show a scale of 1:50K). As you zoom in, the format changes to the Explorer maps (designed for a scale of 1:25K).

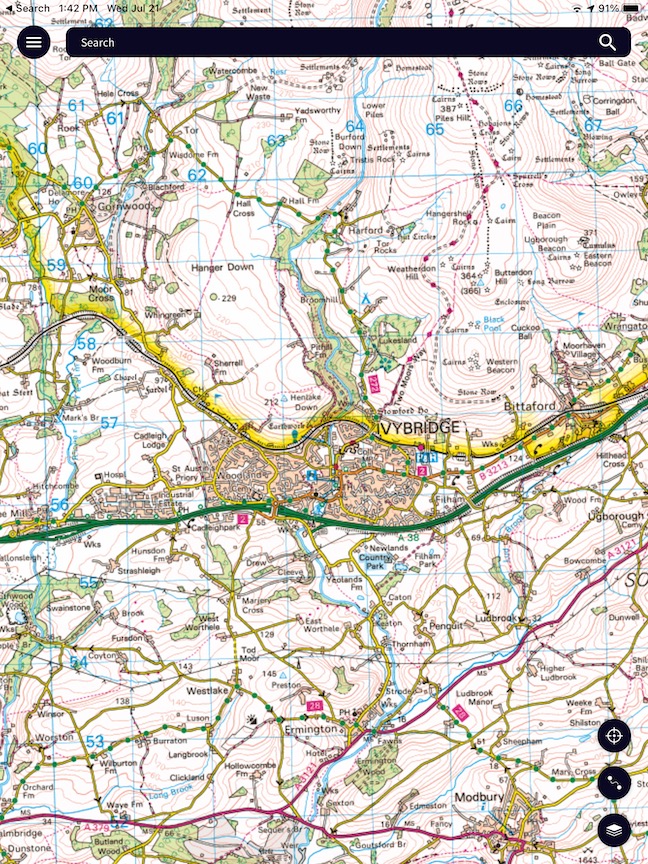

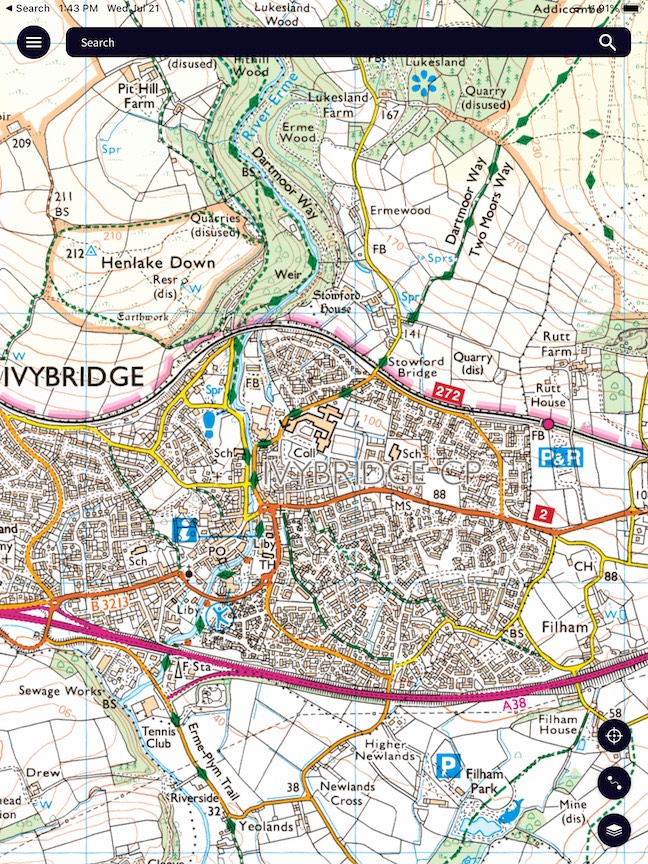

Here are two screenshots of OS Maps displaying the area where the Two Moors Way passes through the town of Ivybridge and enters Dartmoor. The first version shows the Landranger style and the second zooms into a smaller area and shows Explorer style. It’s a bit disconcerting when the style changes suddenly as one zooms in using the app, but it’s not bothersome.

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright

Unfortunately the details of the legends are different on the two separate map formats. For example, on Landranger a long distance trail such as the Two Moors Way is marked with red diamonds while on Explorer it appears as green diamonds. On Landranger contour lines are in red while on Explorer they are more of a brown color. It’s not too bad. Your brain will sort it out almost automatically. The important thing is that when you zoom in you get more detail. For example, when you zoom in to Landranger format you see individual field boundaries (stone walls, fences, or hedgerows shown as thin black lines) which can be extremely useful when you are following a path through a farming area. It’s useful to see if you are on the wrong side of a field boundary because otherwise you may find yourself headed into a dead end with no outlet.

The OS Maps app is designed to work with your account on the OS web site. You can use the web version of the map on a large screen computer to draw a route. That route is automatically available on an iPhone or Android that is signed into the same Ordnance Survey account.

Don’t Forget to Download!

You need to remember that using a map on your phone (such as the OS Maps app or AllTrails) works differently depending on whether you are connected to the internet. When connected you can move around the map freely to look at different areas. But in the center of Dartmoor or some other isolated spot, you can’t rely on a cell signal to connect you to the internet. Before you venture out on a walk without internet access, you need to display the area on the screen where you expect to walk and then use the menu to explicitly download that map to your phone. As a test, switch to airplane mode to disconnect from the internet to verify that you can still see the map for the area you need once you are out of cell phone coverage.

Open Street Maps

Open Street Maps (OSM) is similar to Wikipedia, except for maps. Anyone can contribute. A community of volunteer mappers maintains information of roads, trails, and tons of geographic detail all over the world. Coverage of information about paths and roads in the UK is generally quite good.

For an overview of walking routes in the UK (and elsewhere) see the site Waymarked Trails. The link here shows the western start of the Coast to Coast Path.

An Illustrative Comparison of Different Tools

To show how various mapping tools compare, let’s focus on an area near the western start of the Coast to Coast Path (C2C). For a long distance walk such as the C2C, you’re likely to have a guide book which will include some sort of map as well as some detailed route notes.

Guide Books

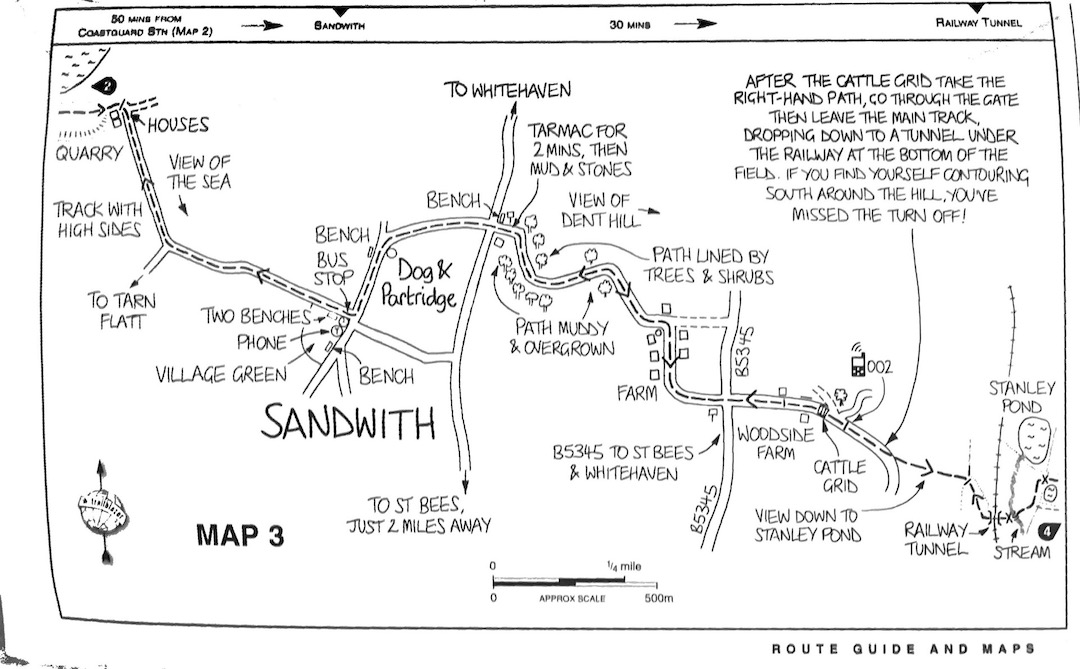

Trailblazer offers a series of popular guide books, including one for the Coast to Coast.

The Trailblazer maps combine route notes with a simple, chatty map. While not as detailed as an Ordnance Survey map, it has enough information to get you where you need to go. I’ve used them for the several trips. They are effective.

The Trailblazer map is very focused on the standard route. If you stray off that route, either by mistake or because of a side-trip, you will not know where you are. The same applies to route notes in general. That’s why you should also have a general map (either paper or electronic).

Trailblazer offers free delivery world wide. If you buy one online from place such as Amazon, make sure you have the latest edition. And remember to check their web site for updates.

Cicerone is another publisher of popular guide books. While Trailblazer tends to focus on the more well-known long distance routes, Cicerone has a much wider selection of books, many of which focus on a particular county or area of England. Searching their catalog is fun because it covers areas that we as Americans probably have never heard of. For example, try Walking in the Forest of Bowland and Pendle

A guidebook to 40 diverse circular day walks suitable for walkers with navigational skills. The Forest of Bowland and Pendle are two of north west England’s upland AONBs, perfect for walkers who enjoy exploring rough hilly, sometimes pathless terrain. The routes include Ward’s Stone, Pendle Hill, Longridge Fell and Fair Snape Fell.

Sounds interesting! Like most Americans, I had never heard of the Forest of Bowland or Pendle. AONB stands for Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Compared with national parks, AONBs are a next level form of conservation for some rural areas,

I’ve used a couple of Cicerone guides (for the Cleveland Way and the Two Moor’s Way). They provide detailed route notes accompanied by excerpts from Ordnance Survey maps. In some cases they include a map booklet which contains a more complete map of the area. As with the Trailblazer guides, they also have notes on flora and fauna, services, and points of interest.

Using Your Phone as a Compass

Most smart phones can also serve as a compass. The iPhone comes with the Compass app.

There also is a free app from the Ordnance Survey called OS Locate (for iPhone or Android). OS Locate will show your location in terms of standard UK grid coordinates and can serve as a base plate compass.

Just in Case

Have a Backup

OS Maps and AllTrails and other GPS resources are great, but always have a backup. Don’t get into trouble because you lose your phone or run out of battery. You should have a compass and some sort of map as backup. If you plan to rely heavily on your phone, you may need an extra external battery. If you’re doing a multi-day walk and staying in B&B’s, make sure you have a routine to get your phone charged and to make sure you don’t accidentally leave your charger behind.

Where Am I and How To Communicate That To Someone Else

In case of emergency, you may need to tell someone where you are. If you have a smart phone or a satnav device, GPS can tell you where you are. You can specify a location in terms of longitude and latitude. For example, in Google maps, press and hold a spot on the map until you see “dropped pin” at the bottom of the screen. Tap on the pin and you’ll see a numerical value for latitude and longitude. That’s where you are.

But there may be a catch. It turns out the earth is not a perfect sphere and as a result there are multiple systems for mapping latitude and longitude to its imperfect shape. Google Maps and GPS use a coordinate system called WGS84. The catch is the UK Ordnance Survey maps uses a UK-centric system OSGB36. In case you want to nerd out on why there’s more than one way to map latitude and longitude to the earth’s surface, check this Wikipedia article.

GPS and Google Maps and other world-wide maps use WGS84. The UK uses OSGB36 (or something similar). The practical issue is that the same latitude and longitude coordinates expressed in WGS84 can be almost 100 meters away from the same coordinates expressed in OSGB36. (See this Wikipedia article for more detail on these effects.)

The upshot is that if you report your location to emergency service via latitude and longitude from Google maps, they might interpret that as being from the UK system.

I first encountered this issue when I downloaded way points from a guide book that uses the UK system (OSGB36) and imported them into Open Street Maps on my Garmin GPS which uses WGS84. I quickly saw that something was off. One might be looking for a bridge or a trail intersection that might be a bit off from what you expected. It’s something to keep in mind. If you have a handheld satnav (such as from Garmin) there usually is a setting that let’s you choose what coordinate system you want to use.

OS Locate

In the UK people often communicate location in terms of the grid reference system that is specific to the UK rather than using latitude and longitude There’s an app called OS Locate for iPhone and Android that will report your location in UK grid reference terms or in latitude and longitude based on OSGB36. It also can be used as a compass. It’s a good thing to have on your phone, just in case.

The UK Grid System

Ordnance Survey maps (and therefore many other maps for the UK) emphasize identification of locations in terms of the national grid system. There’s a section on each OS paper map that describes the grid system. A grid reference consists of two letters which describe the general area followed by 4 or 6 numeric digits (more digits, more precision).

For example, the grid reference for the start of the South West Coast Path in Minehead is SS971467. Expressed as latitude and longitude, that’s 51°12′37″N , 003°28′24″W (degrees, minutes, seconds) or 51.210351 , -3.4733859 (degrees). The UK grid reference is totally unfamiliar to an American audience but is widely used in the UK.

More Map Resources

If you are looking for a tutorial in the details of taking advantage of map and compass there is a series of posts by Glyn Dodwell map reading & navigation

Ways You Can Go Wrong and How to Avoid Them

My most embarrassing navigation mistake happened on the Pennine Way. It was raining so I was a bit buttoned up. I walked down the path to a spot where it crossed a busy road. I stopped there for a bit of a break and had a small snack and a drink. During my break, I somehow got it into my head that I had crossed the road and just started up the path. But I hadn’t crossed the road so when I headed up the path I was actually heading back in the direction I had come from. I probably went almost a quarter of a mile before I checked my GPS track and realized I was retracing my steps. Nagging doubt is your friend! Listen to it. When in doubt, check!

Some of my difficult navigation experiences have occurred while I was following a local route suggested by a pamphlet from the local TIC (tourist information center). The local route may not be that heavily used and may or may not have signs when you need. A crude hand drawn map that may go along with a pamphlet like that is not enough to keep you from getting lost. You need a good map or a good mapping app on your phone.

There are a number of situations that have tended to increase my chances of error. You may encounter a pasture area where the problem is that there are a bewildering multiple of paths you might follow, paths made by grazing sheep or cattle. That’s a time when you need to keep an eye on your GPS or your compass. Another situation that has caused me problems is when I’m striding along a nice wide track and my intended route turns off onto a small, less visible path at the side. Unless you are paying attention, it may be easy to miss the turn. As I said at the beginning of this section, don’t be over-confident. If you have any doubts, check where you are.

A GPS Trace to Keep on Track

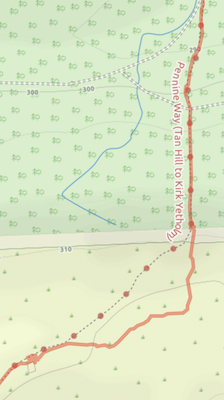

One nice feature of using a SatNav (GPS) device or a smart phone is that you may be able to quickly look at the device to see whether you have wandered off route. The two maps here show a situation where I got slightly off track on the Pennine Way. There was no clear path on the ground, just lots of sheep trails meandering about. On the map on the left, the solid orange line shows the GPS trace recording my walk. I saw on the map that I was aiming toward a forest area. As I later got into that area I realized that a large section had been clear-cut so looking for a wooded area was not helpful. Once I looked closely at my GPS I realized I was heading too far east and needed to turn north to regain the main trail. The photo shows the spot where I took off my rucksack and paused to figure out where I was and which way I needed to head.

I enjoy saving GPS traces as a souvenir of my walks. When I zoom into the detail I can sometimes see places here I went wrong.

Ordnance Survey Trig Points

The Ordnance Survey is not just maps. It actually has a visible presence on the ground. On many high points one finds a concrete pillar that marks one of the known survey points that anchor the maps created by the Ordnance Survey. Because the trig pillars are located at a high spot with a good view, one generally feels a sense of accomplishment having reached one.

Between 1935 and 1962 more than 6,500 concrete pillars marked the basis for the UK Ordnance Survey grid. Traditional survey techniques required that in clear weather it be possible to see at least two other trig points from any one trig point. (Or so they say. I can’t say that I’ve been able to verify that.)